By Emilio Longo

June, 2017

Submitted in partial requirement of the Master of Teaching (Secondary)

Melbourne Graduate School of Education

The University of Melbourne

Abstract

The conceptual training of the twenty-first century artist tends to overlook academic instruction in skill-based drawing and aesthetics. Although these subjects are gaining international credibility in private institutions, they remain largely denigrated, only partially taught and even completely ignored in contemporary visual arts pedagogy. This study has endeavoured to investigate why this is the case, by reviewing literature related to the historical and contemporary teaching of drawing and aesthetics. The Secondary Victorian visual arts curriculum was analysed in proposition of an academic drawing and aesthetics curriculum, to be used as a strategy for building drawing skills and developing aesthetics sensibilities in secondary visual arts education. The qualitative research took the form of a documentary study, approached from an objectivist epistemology and an interpretivist framework, which was governed through an inductive thematic analysis. Both primary and secondary sources were used, which document and critically comment on the teaching of drawing and aesthetics from the time of Ancient Greece, through to the twenty-first century. The analysed data revealed that the subjects increase psychomotor development, historical awareness, visual analysis skills, emotional wellbeing and appreciation for discipline and craft, which ultimately enhance students’ creativity and lead to a widely applicable skill set. The results also justify that skill-based drawing and aesthetics can be taught in tandem with digital processes to improve visual literacy in the twenty-first century. However, further research is required to study the place of the subjects in primary education and how the competencies, techniques and capabilities learnt are transferable into career choices and life skills.

Acknowledgments

Firstly, I would like to acknowledge my supervisor, Dr Kathryn Coleman, for providing me with advice, guidance and support throughout this semester and more generally, throughout the course of the MTeach. Her passion for visual arts education is truly irrepressible and our discussions helped me gain perspective on what it means to be a contemporary visual arts teacher.

I would like to thank Emma Rickards for her knowledge, enthusiasm and humour. Her feedback from the first year of the MTeach has helped me consider how students can relate to the subjects advocated for in this thesis.

My gratitude is extended to the Melbourne Graduate School of Education for allowing me the opportunity to carry out research into my chosen area, it has been a privilege. All the staff at the MGSE have delivered informative lectures and tutorials which have given me thorough insight into the teaching profession.

Finally, I would like to acknowledge all the contemporary art schools in Melbourne, particularly, RMIT School of Art and the Victorian College of the Arts, for providing me with a thorough understanding of what artistic practice means in the twenty-first century.

Table of Contents

| Abstract | i |

| Acknowledgments | ii |

1. Introduction

|

1 |

2. Literature Review

|

2 |

3. Methodology

|

3 |

4. History of Drawing

|

4 |

5. Discussion

|

5 |

6. Conclusion

|

6 |

1. Introduction

Research Question: What is the Place of Skill-Based Drawing and Aesthetics in the Secondary Victorian Visual Arts Curriculum?

The practice of skill-based drawing in twenty-first century visual arts pedagogy, is an area of study which has been repudiated by most university undergraduate art programs. By “skillbased drawing” it is meant the academic study of draughtsmanship as it was taught from the late seventeenth-century, through to the late nineteenth-century (Efland, 1990). The reason for the absence of drawing in academia is partly due to the poststructuralist doctrine that the visual arts faculties uphold. Learning how to draw is viewed as passé and no longer relevant to the formation of the contemporary artist. Alternatively, a conceptual training has prevailed which has become far removed from the traditional notion of craftsmanship (Ross, 2014). This has created a disadvantage for contemporary art students, as drawing offers a critical means of communicating in the twenty-first century (Keller, 2015). Fortunately, we are amidst a resurgence in skill-based drawing which has been developing under the cultural surface since the 1970s; primarily in private institutions located in New York, Minneapolis and Florence (see appendix 1) (Trippi, 2012).

Considering that the revival is occurring internationally, Australia has been slow to catch on (Gutteridge, 2016). Consequently, there are few options for art students and pre-service art teachers to receive training in skill-based drawing, resulting in the only option being to relocate abroad. The cost that these institutions charge for their programs (usually three to five years in length) is by no means cheap with some asking for up to $22000 per academic year, without the option of government subsidised places (“Admissions & aid”, n.d.). Not helping the situation is the fact that the institutions are not accredited and therefore, do not offer a degree upon completion of the programs, but rather, a certificate of excellence which is not always transferable into university credits (“Curriculum”, 2016). These factors ultimately create a restriction to the accessibility of skill-based drawing. The study of drawing should not be limited to only those who can afford it, but should be available to all. If drawing is a visual language that provides a means of communication, then why should it not be viewed as a literacy that is equally as important as learning to read and write? Moreover, if universities are refusing the inclusion of skill-based drawing in their curriculum, then it seems logical that the subject should be included in secondary visual arts education.

This thesis is framed by the questions; What is the relevance of skill-based drawing and aesthetics in a visual arts curriculum? And What is the place of skill-based drawing and aesthetics in the secondary Victorian visual arts curriculum?

The “Visual Arts Practices” strand as documented within the Victorian Curriculum stipulates that students’ skills are developed; “by exploring, selecting, applying and manipulating techniques, technologies and processes” (VCAA, 2017, NPN). However, there is no explanation on how drawing skills can be built throughout years 7-10. For a student to develop proficiency with drawing there are certain principles that must be understood which include; light, form, space, construction and composition (Keller, 2015). Learning these principles requires a teacher-led, systematic model of instruction, whereby students are given set exercises and considerable time to develop dexterity with the foundational principles of drawing (Aristides, 2006; Graves, 2013; Hale, 1964).

The subject of aesthetics in contemporary visual arts education is an area which has also been revolted against, by trends that have developed because of contemporary art. The notion that representation signifies truth begun to be questioned in the 1970s, which gave way to reactionary poststructuralist artistic practices, that have dominated the art world since (Bertens, 1995). Today, the idea of the traditionally beautiful artwork is rejected by postmodern types, as they believe that beauty is an idea which is too literal and unsophisticated (Ross, 2014). However, fostering the study and appreciation of beauty has a range of benefits which can help people live fulfilled and joyful lives (Scruton & Lockwood, 2009).

The study of historical artworks is one way to engage students in aesthetics. When pre-twentieth century artworks are presented to students they tend to be interpreted through the lens of contemporary cultural criticism, which removes the artworks from the cultural, social and ethical affairs that were relevant at the time of creation (Smith, 2006). If students are to penetrate the artists thought, they must come to understand the high ideals that governed the artworks creation and this can only occur by presenting from an art historical perspective (MacManus, 2009). The teaching of skill-based drawing also helps to initiate this process of penetration, by helping students to understand the formal elements and artistic conventions that developed throughout the course of art history, and how artists implemented them to communicate specific ideas. The historical artworks that have been bequeathed to culture have created a rich archive of knowledge, which can be used to help students develop their aesthetic sensibilities. Tuman (2008) explains that historical artworks are “strongly embedded in the values in our American Western Heritage and to retreat from teaching the Western canon would disadvantage students” (p. 63). Tuman’s statement could very well be rephrased to include; “our Australian Heritage as well”.

The Victorian Curriculum explains that “Making and Responding” in secondary visual arts is carried out through students developing; “an understanding of aesthetic knowledge when they view artworks and view[?], discuss and evaluate the characteristics of artworks from different cultures, locations and periods of time” (VCAA, 2017, NPN). To help teachers address the subject of aesthetics, it would be beneficial to have a curriculum in place which outlines how the Western themes of Beauty, Greek Mythology, the Sacred and Divine, and Humanism can be presented to students in ways that helps them see the universal qualities of these subjects. An aesthetics curriculum is necessary since some art teachers may not be familiar with the aforementioned themes, due to their own training being dominated by contemporary art ideologies (Gottsegen, 2003). Ultimately, through studying aesthetics, students will develop the capacity to interpret an artworks aesthetic communicative properties before carrying out the process of art criticism (Tuman, 2008).

This thesis analyses the place and role that drawing skills, techniques and aesthetics play in contemporary visual arts education, by examining how skill-based drawing and aesthetics can be implemented into the secondary Victorian visual arts curriculum. To do this, I have created an academic drawing and aesthetic curriculum which is ontologically rooted in the Western canon of art history, in order to help build visual literacy in the twenty-first century.

2. Literature Review

The following literature review is based on a thematic process of gathering research according to the two main issues that have been identified in contemporary visual arts education.

Art and Technique

The relevance of teaching artistic techniques is an area which is widely contested amongst visual arts educators. Since the dawn of the twentieth-century, modernist trained art teachers have dominated university art departments which has been one of the reasons that classical techniques nearly became obsolete (Elkins, 2001). Consequently, Gammell (1990) states; “a generation of painters grew up wholly insensitive to fine workmanship, unable to achieve it, and affecting to scorn it” (p. 3). Ross (2014) explains that the craft of drawing has always been central to the language of the visual arts and that since the time of cavemen, it has been used to communicate all the human conditions and is therefore, a timeless means of communication which is equally as important as written and spoken forms. Due to the development of progressive art movements, the value of fine draughtsmanship as a major focus within an art students training has been devalued, ignored and even entirely dismissed by some institutions (Keller, 2015; Trippi, 2012). Gottsegen (2003) validates this claim by explaining the reason for this negligence is due to the “pseudo-intellectualisation of artmaking”, which has resulted in the notion of craftsmanship to be discredited and simultaneously, has caused the traditional fine arts curriculum to become disassembled (p. 1)

Ergo, contemporary art is anti-authoritarian by nature which defies definition and has no regard for what art is, or should be (Bertens, 1995; “Postmodernism”, n.d.). Ross (2014) states that postmodern art curriculum embraces “form for its own sake, colour for its own sake [and] line or mass for their own sake” (p. 1). This concept is based on the notion of bringing art back into the “service of the mind” and away from “retinal art” (an ideology which was proposed by the twentieth-century artist; Marcel Duchamp, who advocated for art to become an intellectual pursuit by removing itself from the story of art history) (Rosenthal, 2004). Gottsegen (2003) furthers this argument by noting that contemporary visual arts educators believe academic drawing is overly rooted in “making” and does not involve enough “thinking” and is therefore, not an intellectual pursuit (p. 1). However, this quarrel is a fallacy, as McLaren (2007) explains, the practice of manual drafting requires the utmost intellect which improves; “general cognitive development: problem solving, thinking skills, spatial awareness, visualisation skills; psychomotor development: coordination, control, accuracy, neatness; affective development: motivation, artistry, care [and] personal satisfaction” (p. 184).

Due to the nature of skill-based drawing being a hands-on process which does not involve digital media, some visual arts educators view the subject as outdated (McLaren, 2007). Prensky (2001) would label skill-based drawing as “legacy content” which includes; “reading, writing, arithmetic, logical thinking [and] understanding the writings and ideas of the past” (p. 4). It is no question that these subjects are an important part of foundational education although, what seems to be the challenge for both teachers and students, is engaging with skill-based drawing in a way that does not seem old fashioned. The practice of using the drawing board and paper may seem anachronistic to some teachers and thus, they may rush through it in order to get students onto digital software. Alternatively, Prensky situates the digital singularity within “future content” which includes; software, hardware, robotics, nanotechnology, genomics [as related to] ethics, politics, sociology [and] languages (p. 4). Considering that skill-based drawing relies heavily on manual processes, Sorby and Gorska (1998) side with the belief that manual drafting can enhance spatial ability more effectively than digital drafting methods such as; Computer Aided Design (CAD). They believe that the hands-on experience of drawing fosters a more comprehensive knowledge of the foundational principles of draughtsmanship and thus, helps students bring their ideas into actuality more effectively.

It seems logical that manual drafting is introduced to students before digital drafting software, as it helps develop fine motor skills, understand geometry, carry out shape and measurement assessment and improve discipline in application, which can then be applied to the digital realm (McLaren, 2007). Field (2004) further acknowledges the benefits of manual drafting, by claiming that it can help students understand the three-dimensional structure of objects and how they can be translated into two-dimensional representations. Prenksy (2001) concludes by bringing the two types of content together and suggests that educators find a way to teach both, legacy content and future content in “the language of the Digital Natives” (p. 4). These arguments reveal that skill-based drawing is widely applicable and can be adopted by digital curriculum to teach a range of subjects including; animation, architecture, illustration, concept art and graphic design (McLaren, 2007).

Efland (1990) emphasises how drawing was taught; “from the rigid, mechanical exercises of the nineteenth-century to the freer forms of expression then advocated by Ziegfeld, Lowenfeld, and D’Amico” (p. ix). There are some such as Hockney (2006) who dismiss the claim that the ability to render a subject to a very high level of finish is possible, if done completely by hand. Hockney proposes that the drawings of artists from the fifteenth-century onwards were created using a camera lucida (which they used to project an image onto a canvas and then proceeded to trace over it). This assertion is scornful of the system of training that a pre-twentieth century artist underwent, to attain the ability they had to draw so well (Richards, n.d.). Gammell (1990) notes that of all the various elements of study that make up the painter’s craft, drawing has always been one of the most essential and unquestionably, one of the most difficult to acquire. Therefore, the historical teaching tradition of art always placed drawing at the forefront of its pedagogy. Gammell further states that; “the experience of centuries has shown that the painter cannot be started drawing too early nor be trained too thoroughly in that [drawing] art” (p. 2). These arguments validate that drawing has always been a central focus to an art student’s formation and as Aristides (2006) emphasises; “anyone can learn to draw, but it takes both skill and talent to do it well” (p. ix).

Art and Aesthetics

The relevance of aesthetics in contemporary visual arts education is also an area which is highly debated. Aesthetics has its origins in the eighteenth-century and denotes a kind of object, judgment, attitude, experience and value (Shelley, 2009). Engaging in the study of aesthetics is one way to investigate the conceptual and theoretical underpinnings of art, and the ways that we think about them (Parsons & Blocker, 1993). Heid (2005) explains that teaching aesthetics in the art classroom can improve students’ cognition, through the aesthetic experiences they encounter. She believes that a teacher can help students build aesthetic knowledge by becoming finely attuned to their senses, through allowing time for them to talk and write down feelings and attitudes towards their aesthetic experiences. Greene (1995) supports this claim by explaining that aesthetic experiences engage students’ imaginations and is therefore, one of the most effective learning strategies that a teacher can provide. Scruton and Lockwood (2009) argue for the relevance of beauty in the arts and in everyday life. They suggest that regardless of race, religion, or social class, we all have the need and capacity to experience beauty throughout the course of our lives. They also explain that contemporary art has become detached from the older traditional curriculum, which was based on the bastions of beauty and craft.

According to Beardsley, Wreen and Callen (1983) the principles that aesthetics are based on such as; “harmonious design, good proportions [and] intense expressiveness” are characteristics which help to maintain our wellbeing and lead to; “increased sensitisation, fuller awareness, a closer touch with the environment and concern for what it is and might be” (p. 14). From a Christian perspective, there has always been a strong relationship between God, beauty and art. Clayton (n.d.) explains that beauty is a quality in something that directs us to God, by first drawing our attention to the quality and then pointing to look beyond, which is the invitation that leads to Him. Upon accepting this invitation, we respond with love to that beauty and open up to it and the ultimate source of inspiration for the artist, God (or the blessed sacrament of the Eucharist). This process uplifts the spirit and provides solace to the soul. Nature has always been a source of inspiration for artists and considering that it is God’s creation; the slow and intimate study of it points to the divine. Saint Pope John Paul II (1999) believed that when God observed that all he created was good, He saw that it was beautiful as well. Therefore, beauty becomes the visible form of good, just like good is the metaphysical condition of beauty. In his major study, Eco (2004) reminds us that in centuries past, something that was beautiful was considered by the vast population to be good.

The dilemma with developing a contemporary aesthetics curriculum is that we are at a point in time which embraces “art for art’s sake”, and this has caused artistic practice to become overly concerned with self-expression (Ross, 2014, p. 1). Clayton (n.d.) articulates that art is more than simply a matter of personal taste and that beauty is not necessarily in the eye of the beholder. He claims that although we may not all come to an agreement on what we find attractive, there is an element of objectivity that we must acknowledge in things which we find beautiful, and this very element can be used to train artists to recognise and appreciate the fodder of beauty. For instance, in the nineteenth-century there was a common understanding of what constituted “good taste” in works of art. Ackerman and Parrish (2011) note that the Greek sculptures (and later Roman copies) were considered by the art cognoscenti to be fine examples of idyllic form, and all art students were required to draw from them, to not only learn the principles of academic draughtsmanship, but to also develop their aesthetic sensibilities. Since there is no consensus on what embodies good taste in the twenty-first century, it seems logical to look to the past and learn from the high ideals (artistic and philosophical ideas) that were detrimental to an artist’s formation, in order to move forward with tradition.

Gottsegen (2003) highlights that one of the problems which university art departments have with teaching aesthetics, is that art history is often taught separate from studio art and is sometimes even located in a different department all together. This creates a disadvantage for art students, as they are not able to see correlations between the techniques, ideas, themes and styles that may be shared with their own practices and that of artists from previous centuries. Beardsley et al. (1983) state that the problem with postmodern visual arts curriculum, is it has the tendency to refute the “feeling aspects” that are part of the aesthetic experience (p. 2). Rather, the postmodern doctrine is partly based on the concept of “deconstruction” (a term introduced by the French philosopher, Jacques Derrida towards the end of the 1960s), which Leitch states; “works to deregulate controlled dissemination and celebrate misreading” (as cited in Güney & Güney, 2008, p. 223). This results in postmodern artworks often having ambiguous meanings which become isolated from the context of art history and therefore, create their own autonomous language (Kearney, 1984).

The main issue with teaching aesthetics in secondary visual arts education seems to be getting students to understand how the ideas that early artists explored, are relevant in contemporary times. Tuman (2008) argues as to whether the aesthetic experience that a student receives from viewing a Rembrandt painting, is reason enough for the artist to be a major focus in national curriculum. He goes on to state that this conclusion can only be drawn by considering; “whether his [Rembrandt’s] life and work and the culture of seventeenth-century Holland have contemporary relevance” (p. 57). We can pose the question; why does the Victorian English curriculum include old works of literature such as; Shakespeare’s Macbeth as a core part of the subjects requirement? According to the curriculum structure;

“Students learn how to explain and analyse the ways in which stories, characters, settings and experiences are reflected in particular literary genres, and how to discuss the appeal of these genres. They learn how to compare and appraise the ways authors use language and literary techniques and devices to influence readers. They also learn to understand, interpret, discuss and evaluate how certain stylistic choices can create multiple layers of interpretation and effect” (VCAA, 2017, NPN).

This passage confirms that there is merit in exposing students to Shakespeare (among other authors) to teach a variety of analysis skills in English. It seems fitting that this very statement could be used to justify and facilitate students’ exploration of pre-twentieth century artworks, in the visual arts curriculum as well.

A mission which advocates for the inclusion of historical artworks in secondary visual arts curriculum is The Rembrandt Project. This teaching resource was developed in 2008 by The National Endowment for the Humanities in America, as a way of providing both teachers and students with insight into the thought and artworks of the seventeenth-century Dutch artist; Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn (Piro, 2007). The resource is presented as a comprehensive website which frames Rembrandt’s oeuvre around the subjects of culture, civilisation and identity as a way of helping viewers penetrate the artist’s world. Strategies such as this could very well be used to present historical artworks to students in the “Explore and Express Ideas”, and “Respond and Interpret” strands of the secondary Victorian visual arts curriculum (VCAA, 2017). This will ultimately help teachers address the skills and ideas that dominated early Western artistic practices, and how they can be used today to train traditionally informed contemporary art students, through the secondary Victorian visual arts curriculum.

3. Methodology

A documentary study has been used as the overarching methodology, which has been approached from an objectivist epistemological perspective and interpretivist framework (Mogalakwe, 2006). This methodology is favoured due to the nature of the research requiring collection, analysis and synthesis of primary and secondary documents, which outline the drawing curriculum and aesthetic sensibilities used by both, historical and contemporary workshops, academies and private teaching studios. Ultimately, this process has been used to understand the place of skill-based drawing and aesthetics in the secondary Victorian visual arts curriculum.

Research Method

This study has utilised a document analysis as the chosen method to collect qualitative data (Gray, 2014). One of the issues associated with qualitative research, is that there is currently no consensus on how the analysis of data is to be carried out and the length at which it should be analysed (Gray, 2014). Strauss and Corbin (1998) highlight that some researchers believe qualitative data does not need to be analysed, but rather, can simply be presented for what it is. Gray (2014) notes that this approach alleviates researcher bias by allowing the data to “speak for themselves” (p. 602). Alternatively, some researchers argue that qualitative data should be precisely selected, synthesised and described in a way that is completely objective and devoid of any preconceptions (Gray, 2014). Gray identifies a third type of researcher who remains overly involved with interpreting the data to build theories and link concepts and categories, in order to create a theoretical framework. Moreover, Wolcott (1994) explains that some researchers believe quantitative data is overly concerned with description and narrative and therefore, fails to create a critical argument.

Bailey (1994) argues that using documentary methods to conduct research essentially involves the analysis of documents, to uncover information about the subject that is relevant to the researcher. Similarly, Payne and Payne (2004) explain that documentary methods are commonly used to investigate, categorise, interpret and identify the incapacity that some publicly, or privately available documents may have. Glaser and Strauss (1967) are quick to identify the similarities between using documents as data and undertaking observations and interviews. They point out the advantages of using libraries to conduct research which includes; being surrounded by a range of conversations, opinions and arguments that are very similarly encountered when doing fieldwork. Collecting and analysing documents in a library can also lead to chance findings and “serendipitous discoveries”, which can deviate from the systematic search that was originally intended for by the researcher (Merriam, 2009, p. 150).

Mirriam (2009) states that there are various types of documents that can be collected for research purposes which include; public records, personal documents, popular culture documents, visual documents and researcher generated documents. Hodder and Hutson (2003) use the term “mute evidence” to explain documents that have survived over time, which can be used to study culture. They further state; “such evidence, unlike the spoken word, endures physically and thus, can be separated across space and time from its author, producer, or user” (p. 155). Documents can also include artifacts which LeCompte and Preissle (1993) explain as; “symbolic materials such as writing and signs and nonsymbolic materials such as tools and furnishings” (p. 216).

The main distinction a qualitative researcher needs to make is to discern whether the data they are collecting is classified as primary, or secondary sources (Gray, 2014). Primary sources are documents in which the author is writing about a particular issue, event, or subject that they have experienced for themselves (Merriam, 2009). On the other hand, secondary sources are documents which have been written by an author who has not had first-hand experience of the issue, event, or subject and is usually writing the document after the situation has occurred (Merriam, 2009). Secondary sources are commonly used for undertaking historical research, as they allow for what Scott (as cited in Mogalakwe, 2006) refers to as “mediated”, or “indirect access” as opposed to “proximate”, or “direct access” which alternatively, can only be obtained through primary sources (p. 223).

Due to this study being ontologically committed to the pre-twentieth century teaching of skill-based drawing and aesthetics, it has been necessary to conduct historical research into the curriculum that was used to train art students in the centuries past, to understand the place of the subjects in the secondary Victorian visual arts curriculum. In order to ascertain this information, secondary sources offer the only option for accessing the historical visual arts curriculum. Gray (2014) explains that secondary source data analysis usually consists of reviewing and analysing (or reanalysing), data which has been published by another researcher, for the purpose of conducting further research into a sub-set of original data, or to shed new light on issues concerning the data. The use of secondary sources pose a number of benefits to this study including; the convenience of not having to conduct interviews, or observations and therefore, saving costs and time (Gray, 2014).

Data Analysis

An inductive thematic analysis has been used to analyse publicly available historical and contemporary qualitative data in the form of books, journals and websites, to codify themes that reoccur in visual arts curriculum (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Grey (2014) explains that an inductive approach to a thematic analysis emerges from the themes identified in the data itself and therefore, the analysis becomes data driven. Gray further states that; “a theme captures something important about the data in relation to the research question, and represents a level of patterned response or meaning within the data” (p. 609). This process has been taken to develop the year 7-10 academic drawing and aesthetics curriculum, which is based on best practices that have been identified in the data. Thematic maps were also utilised to collate codes and synthesise them into themes, as a strategy to narrow the scope of the research (Braun & Clark, 2006).

The gatekeepers to the documents which have been analysed in this study consist of; art historians, artists and visual arts educators who have documented and critically commented on the progression of visual arts education, from the time of Ancient Greece, through to the twenty-first century. The following questions have been used as a framework to analyse the data: (a) What was the relevance of skill-based drawing and aesthetics in pre-twentieth century visual arts pedagogy? (b) What is the relevance of skill-based drawing and aesthetics in contemporary visual arts pedagogy? And (c) What is the place of skill-based drawing and aesthetics in the secondary Victorian visual arts curriculum?

Despite the fact that skill-based drawing and aesthetics are predominately pre-twentieth century subjects, as has previously been mentioned, there is a renewed interest occurring in Europe and the United States (Gutteridge, 2016). Due to the revival, several books, articles and educational foundations have been established to help promote skill-based art in the twenty-first century (Aristides, 2006, 2008, 2011, 2016; Kralik, 2014). Therefore, primary source qualitative data has been utilised to obtain direct access from the associated gatekeepers, who have been trained in the Western European academic tradition and who are now implementing their teaching into a reconstructed visual arts curriculum. Due to the nature of this study being based predominantly in the field of historical research, there has been no need to secure ethics. The stakeholders to this study include; pre-service visual arts teachers, art students and visual arts curriculum designers, who are interested in understanding the place of skill-based drawing and aesthetics in the secondary Victorian visual arts curriculum.

4. History of Drawing

Ancient Greece

The origins of art education in the West goes back to Ancient Greece; a time when two philosophers (Aristotle and Plato) begun writing about its place in their community (Efland, 1990). At this early point, the idea of becoming a painter, or sculptor was not valued by society and was considered merely a trade, akin to being a labourer. Consequently, the study of the crafts was a relatively small part of foundational education and therefore, they were usually studied in family workshops where the father would pass on his knowledge to his sons (Efland, 1990).

Drawing as a practice became established in the Hellenistic period thanks to the Ancient Greek painter, Pamphilus (the teacher of Apelles from whom we get the term in drawing “Apelles line”) who introduced drawing classes in the fourth-century B.C., in the Ancient Greek city of Sicyon (Efland, 1990). Soon after, drawing classes begun to be established all over Greece. Marrou (1956) explains; “little is known about the ways drawing was taught [but he believes that] children were taught to draw with charcoal and to paint on a board made of boxwood and that the chief activity consisted in drawing from live models” (as cited in Efland, 1990, p. 12). According to Aristotle, the practice of drawing the figure ultimately made students appreciate the beauty of the human form (Efland, 1990).

Roman Empire

In the third century A.D., new ideas about art developed through the Greek philosopher Plotinus, who formulated a philosophy concerning beauty which was fixed upon Plato’s teachings (Efland, 1990). The philosophy was based on the idea that the artist can use the materials in the physical world to symbolise the Platonic forms (a set of five shapes that make up the only perfectly symmetrical arrangements of a series of points in space), which Plato based the creation of the universe on (“Platonic solids and”, n.d.). The consensus was that the artist is not one who represents objects as they are, but rather, he beautifies what nature fails to. Therefore, art revealed more to the viewer than a mere imitation could. At this time, the concept of beauty was seen as a form of intellectualisation; an idea which was more profound than merely making something “pretty” (Efland, 1990). Even though art was becoming an intellectual vocation, drawing instruction was still not deemed an important subject in the overall education of a Roman youth (Efland, 1990).

Middle Ages

At the end of the Roman Empire, education in general begun to deteriorate and thus, people became illiterate (Efland, 1990). Due to the poor level of literacy, art became an effective teaching tool whereby pictures and statues were used to teach Christianity to the population. During this time, artisanal training was mainly taking place in monastic schools and the practice of drawing was required for monks to make copies of manuscripts (Efland, 1990). This required the monks to not only be skilled draughtsman, but to also have knowledge of painting and how to apply and burnish gold leaf. There was a hierarchy to copying manuscripts which was based upon how skillful the artisan was; the master being at the top and then came his assistants, followed by the artisans, which all received on the job training from him (Efland, 1990).

As the high Middle Ages dawned, craft guilds begun to be established under contracts from churches, or individuals in a position of power. It is now that the apprenticeship system of training was introduced (Efland, 1990). Every guild had a workshop, which in turn, had its secrets (particular working methods which were not to be revealed to other guilds) (Efland, 1990; Barnestone, 2008). The master would agree to take on an apprentice when he reached the age of thirteen, or fourteen. In some instances, the apprentice would receive a wage for his efforts, in other cases, the family of the apprentice would have to pay the master a fee for the training he would provide. The system of training was for all intents and purposes, to learn to imitate the work of the master in order to attain a high level of technical dexterity (Efland, 1990). Barasch (1985) notes that instruction in the workshops was sometimes supplemented by a treatise that explained a creative process, or provided a set of drawing models which the apprentice could copy from (as cited in Efland, 1990). After being apprenticed for a period of up to six years, the apprentice’s final module was to create a masterpiece in their medium. If they were successful, then and only then would they graduate to being a master (Efland, 1990). The master-apprentice system prove effective and continued to be used to train artists right through until the late nineteenth-century (see appendix 2).

Renaissance

It is during the Renaissance that we first see education in place that catered for students’ aesthetic sensibilities. Wilds and Lottich (1962) explain that this was primarily done through developing students appreciation of the beauty inherent in the classical arts of the past, as a way of understanding humanism (as cited in Efland, 1990). Efland (1990) notes that a major treatise written in 1435 by the Italian Renaissance polymath; Leon Battista Alberti, called Della Pictura (On Painting) is a key resource in understanding humanism. In Della Pictura, three of the principles that Alberti believed a painting should contain represents the humanist ethos:

- “A painting should evoke a sense of spatial and historical actuality by using a combination of perspective and a system, of proportion and scale based on the human figure.

- A painting should have an istoria, or theme, a dramatic situation or historical episode from classical literature or the Bible.

- The particular theme should be elaborated through the appropriate use of colour, light, proportion and composition so as to communicate a living, visual drama that would edify, terrify, please, or instruct the viewer” (Efland, 1990, p. 28).

Alberti’s principles led to reevaluating whether the bottega (workshops) as a system of training were still adequate for the formation of an artist; for the presence of Leonardo and Michelangelo in Florence had now elevated the status of the artist to lone genius (Efland, 1990). The problem was that the workshops (being based solely on technical mastery) were only providing half of the training that was necessary for an artist; as they also had to now have a thorough grounding in humanism, as well as technical proficiency. With this new revelation, the apprenticeship system begun to be questioned, due to the fact that the apprentices were merely learning to imitate the work of their masters (a practice which negated their personal styles). This resulted in the end of the guild workshops and the beginning of the academies which Efland (1990) describes as; “places where knowledge of the theory and philosophy of artistic practice, based on the search for universal knowledge of the science of art, could be developed and shared by teachers and students working in concert” (p. 29).

The first Renaissance academies did not have a regimented hierarchy like the medieval workshops did. Rather, there was a mix of artists who all had one thing in common; they would gather at the academies to draw together and to discuss high ideals (Efland, 1990). The curriculum would consist of; drawing from master drawings and plaster casts of fragments from Greco-Roman statuary, perspectival drawing, the surgical study of the cadaver and sculpture (Efland, 1990). Since students were required to copy drawings before progressing to copying plaster casts, some artist begun to publish drawing manuals which depicted idealised examples of facial features such as; mouths, noses, ears and eyes. Pevsner (1973) notes that Leonardo da Vinci’s artistic experiments and scientific discoveries were used as the basis for the academic study of art. In fact, Leonardo predicted a system of drawing instruction that was used right through until the late nineteenth-century. He stated; “First of all copy drawings by a good master made by his art from nature and not as exercises; then from a relief keeping by you a drawing done from the same relief; then from a good model; and of this you ought to make a practice” (as cited in Efland, 1990, p. 30).

Giorgio Vasari was the first artist to establish an art academy in 1562, located in Florence, which was called the Accademia del Disegno (Efland, 1990). At this point in time, two of the three artists that formed the High Renaissance had passed, leaving only an old Michelangelo remaining. Consequently, Vasari’s academy was established to preserve and carry on the achievements of these artists, through basing the curriculum on the rules and principles they discovered. The academy also encouraged students to copy paintings and sculptures (rather than the direct study of nature), which made the study of artworks a discipline in and of itself (Efland, 1990).

In 1593, another academy was founded in Rome by Frederico Zuccari, which was called the Accademia di San Luca (Efland, 1990). The rules of the academy enforced a course of art instruction designed for a variety of students (from neophyptes to the more advanced). As Goldstein (1996) states; “Novices would begin by drawing from drawings, from reliefs, and with the “alphabet” of drawing, the ABCs of heads, feet, hands, and so on, all drawing from casts; they would go on to draw from the antique, and from the nude model” (p. 30). This course of drawing instruction echoes the same method that was stated by Leonardo da Vinci earlier. Academy rules also stipulated that the director was to take place in the drawing program, and give awards to students that created competent drawings of human anatomy (Goldstein, 1996). The academies curriculum was divided into practical and theoretical instruction, whereby lectures would be given by various academicians. Zuccari himself had a philosophical view of disegno (drawing) in which he described as; “the original image present in the mind of God and in the heavenly bodies He created, the first of which is the sun; as an internal principle, disegno interno, it enters the mind of man as a spark of the divine mind, like the sun, illuminating his worldly activities, of which artistic representation is one, but as disegno esterno, which is secondary and necessarily inferior” (Goldstein, 1996, pp. 31-32). Zuccari’s idea of disegno was not received well by members of the academy, due to its overly speculative and philosophical nature, and many did not understand how it related to the practice of painting.

The town of Bologna saw the Carracci brothers (Annibale, Agostino and their cousin Lodovico) establish the Accademia degli Incamminati in 1582 (Goldstein, 1996). Their academy was somewhat different to others, in the sense that it was a private institution and therefore, was not sponsored by a member of high society (Efland, 1990). Like other academies of the time, the Carracci divided their curriculum into theoretical and practical activities which included; “lectures and discussions of history, mythology, poetry, and music; there were anatomical lectures and studies of bones and muscles in addition to the by now familiar drawing exercises of ears, feet, and other parts of the body” (Goldstein, 1996, p. 34). The drawing curriculum also adopted the practice of copying plaster casts which the academy held contests for. Unique to the Carracci’s curriculum was the academy (a drawing of the nude model done directly from life) (Goldstein, 1996). The Carracci themselves held in high esteem drawing from the antique and copying the work of the Renaissance masters. Although the brothers would have carried out this rigorous academic study themselves, what they taught often deviated from regular academic drawing practice (Goldstein, 1996). However, both the curriculum of the Carracci’s academy and the Accademia di San Luca were precursors to the curriculum used by the French academies in subsequent centuries (Efland, 1990).

French Academy

In 1648, the French Academy of Painting and Sculpture was established in Paris (Efland, 1990). The academies curriculum included; architecture, perspective, life drawing, arithmetic, anatomy, geometry, history and astronomy. Life classes followed the same routine of the earlier academies in Florence and Rome, whereby every month, a different teacher was responsible for posing the model. This rotation ensured that the individual style of the teacher would not be imposed onto students. Working in the life class was allowed for two hours every day and life drawing was only permitted to take place inside the academy (Efland, 1990). Pevsner (1973) explains that private instruction in life drawing was only authorised to artists who were members of the academy. The teacher’s daily routine consisted of; providing beginning students with drawings to copy from, setting up the pose in the life class and correcting errors in students’ drawings (Efland, 1990). Students were divided into two classes; a lower and an upper class. The former were required to copy the drawings of their professor, while the latter were instructed to draw directly from the model. There was also a halfway stage in between the two classes, whereby students had to copy plaster casts from antiquity. As Efland (1990) states; “the sequence of drawing from drawings, drawing from casts, and drawing from the model was viewed as the heart and core of the method from the latter years of the seventeenth-century to the latter years of the nineteenth-century” (p. 37). This statement sheds further light on the influence that the method of drawing which was proposed by Leonardo da Vinci had on the academic tradition.

The technical side of the students training was carried out in the ateliers (studios or workshops) of the academicians, while their theoretical formation was reserved for the lectures which consisted of; anatomy, perspective, geometry and the visual analysis of artworks (Efland, 1990). Ultimately, the academies mission was to maintain the ideology of academicism and through undergoing academic training, students became familiar with the academic style which they incorporated into their work. In fact, in 1708 the artist Roger de Piles wrote a treatise which evaluated students work according to how well it embodied the academies doctrine (Efland, 1990).

In the nineteenth-century, art students also had the option of studying in private ateliers which were established outside of the French Academy (Efland, 1990). The system of training which took place inside these studios was similar to the medieval workshops, whereby a small group of students would study under one master who was known as the patron (father) (Efland, 1990). Students would be drawn to an atelier due to the notoriety of the patron and his method of teaching (which was generally in the neoclassical style of the academy). Drawing was carried out through the process of creating a dessin ombre (value drawing whereby the illusion of relief is established through using a needle point pencil to create multiple layers of cross-hatching) (Boime, 1971). However, after 1863 the more commonly used medium for drawing was charcoal and value was created using an estompe (drawing stump), instead of crosshatching (Boime, 1971). Students were also encouraged to draw outside of the ateliers as well; capturing quick croquis (sketches) of scenes from daily life. This was known as the carnet en poche practice (sketching in a pocket sketchbook), which broke up some of the more time-consuming drawings that students would be completing in the ateliers (Boime, 1971). Efland (1990) states; “A prospective student attempting to gain admission to an atelier would present a portfolio to the master and, if approved, would proceed to draw or paint from the model” (p. 53). On the other hand, if the master believed the students draughtsmanship was not up to standards, he would ask him to draw from plaster casts for a period to improve his eye (Efland, 1990).

Each atelier had its own routine which students abided by and at the beginning of the week, one student would arrive early to establish the life models week-long pose (Efland, 1990). Positions around the model were based on first in best dressed therefore, students tried to arrive before class to secure their place for the week. A common working day was split in two; the first half was reserved for drawing from the model, while the second half was allocated to mastercopies in local museums (Efland, 1990). Students would receive feedback from the patron once a week which would take the form of individual critics, whereby the patron would move around the room and literally draw on the students work to fix errors in proportion and value (Efland, 1990). The atmosphere of the ateliers was competitive with each student having an intense desire to improve their craft and debate issues surrounding art.

The model of the French and Italian academies was colossal and thus, influenced the establishment of academies in other cities around the world including; Berlin, Copenhagen, Vienna, St. Petersburg, Madrid, Spanish America, Mexico City, Buenos Aires, Düsseldorf and Munich, amongst others (Goldstein, 1996; Efland, 1990).

Modernism and Beyond

Before World War II, there were only a limited number of art programs available in universities (Gottsegen, 2003). The curriculum which higher education art departments used was modelled after the traditional practices of cast drawing and life classes. There was thorough instruction given on the craft of making drawings, paintings and sculptures and art history was taught in tandem with studio art (Gottsegen, 2003). In time, this model of training begun to breakdown due to a number of reasons; one of them being the influence of the Bauhaus which was established in Germany in 1919 (Efland, 1990). The Bauhaus curriculum aimed to detach itself from the history of art that had come before it, which consequently meant removing students from the system of training that was used by the academies. In fact, it was Josephs Albers (an influential teacher of the Bauhaus) who proclaimed; “to follow me, follow yourself”, which highlights the Bauhaus belief that art is unteachable and is therefore, antithetical to the master-apprentice system (Goldstein, 1996).

Due to the Nazi regime in 1932, the Bauhaus was closed and a substantial amount of its artist-teachers relocated to the United States and begun teaching in institutions such as; Moholy-Nagy, at the Illinois Institute of Design and Josef Albers, at the Black Mountain College, and later at Yale University (Efland, 1990). This ultimately resulted in the curriculum of the Bauhaus being adopted by many art schools around the world (which still continue to uphold its doctrine today).

After World War II, New York became the center of the art world which triggered a new community of artists to come together and form the New York School (Efland, 1990). This eventuated into the rise of a number of different art movements including; abstract expressionism, action painting, pop art, minimalism, conceptual art and neo-expressionism, all of which became appealing to young art students. As a result, universities begun teaching a number of alternative mediums including; video, photography and graphic design, which replaced the traditional techniques of drawing, painting and sculpting from life (Goldstein, 1996). With the novelty of postmodernism, artistic practices became increasingly challenging to define and so has been the case until this very day. This is partly due to contemporary arts tendency to sever its connection to the past and thus, progresses without tradition, leaving behind the curriculum that was used from the drawing classes in Ancient Greece, through to the academies and ateliers of nineteenth-century France (Ross, 2014).

5. Discussion

The Significance of Skill-Based Drawing

The Da Vinci Initiative’s website (a K-12 visual arts educational foundation that promotes skill-based drawing in America) states; “Like teaching rhythm, tempo, and scales in music class so that a student has many tools to express themselves through music, so too is there a need for a skill-based education in the visual arts” (n.d., NPN). Skill-based drawing is a methodological way of teaching visual art principles, whereby drawing exercises are presented in a logical sequence which the teacher uses to scaffold students into understanding the principles of artmaking (“What are the”, n.d.). Visual literacy is developed through acquiring the ability to see objects as a series of abstract shapes, which ultimately results in students creating drawings that have a fidelity to nature. This is in contrast to drawing based on preconceived ideas, in other words; students are learning to represent what they see, as opposed to what they know (Edwards, 1979).

Nothing is assumed in the curriculum; all students complete the same exercises to ensure they understand the foundational principles of drawing, which begins with the correct procedure of sharpening a pencil and subsequently, how to hold the pencil (Foxton, 2007). Emphasis is given on how three-dimensional objects can be translated into two-dimensional representations, through becoming familiar with principles including; a point on a page creates a dot; two dots when connected creates line; a series of lines creates a twodimensional shape; two-dimensional shapes form the basis of three-dimensional shapes; and an accumulation of line creates value (Barnestone, 2008). These skills are furthered through developing knowledge of composition, perspective, angles, proportions, value, ratio and geometry, as well as drawing materials. Being introduced to systems of design such as; the golden ratio and the Fibonacci sequence also helps students see the relationship between mathematics and the visual arts (Bouleau, 1963).

Skill-based drawing aids several areas of cognitive development including; procedural fluency, strategic planning, information synthesis, fine motor control, automaticity, visual analysis skills, visual integration skills and visual spatial skills (“Curriculum”, n.d.). The results of undergoing a systematic process of drawing instruction will also help students develop appreciation for fine craftsmanship, beauty and discipline, as they become acquainted with the patience and fortitude that is required to create masterful art (Kilarski, 2017). When drawing skills have been instilled in students, they will be able to identify the very principles that they are using in artworks throughout history. Once students begin to understand that drawing is a skill that relies little on talent and can be learnt by anybody, they will have the confidence to control the creative process and thus, believe in their creative potential (Aristides, 2006; “What are the”, n.d.).

Art history reveals to us that learning the craft of drawing is an arduous process which requires; instruction, work ethic and perseverance, in order for one to develop métier (technical mastery) (Aristides, 2006, 2008, 2011, 2016; Goldstein, 1996; Graves, 2003; Gammell, 1990). In fact, it was the nineteenth-century French painter, Jean-AugusteDominique Ingres who said; “It takes 25 years to learn to draw, one hour to learn to paint” (“Ingres quotes”, n.d., NPN). Historically, drawing was always the predecessor of painting and students were not allowed to progress to the appealing medium, until they had mastered the first phase of their academic drawing training (Boime, 1971).

In 1964, the American artist-teacher, Robert Beverly Hale published Drawing Lessons from the Great Masters, in of which he stated; “It has always seemed to me that if you really wanted to excel in drawing the figure, you should go and study with the greatest living master of figure drawing. But the trouble is that there is no one alive today who can draw the figure very well; there is, perhaps, no one alive today who can draw the figure even as well as the worst artist represented in this book” (p. 5).

Although this statement was plausible in the 1960s (due to the limited opportunities that were available to study academic art), today it is not so true. What appeals most in Hale’s statement is his insistence on finding a master of drawing to study with. This view is not one which is shared in the contemporary art world, as the idea of receiving a historical art education is counter-intuitive to the contemporary idea of the creative genius (Aristides, 2006). Studying contemporary art reveals to us that the concept of “training” is not necessarily a prerequisite to gain admittance into the art world, for an artist is now able to bypass many years of rigorous training by simply having an idea as the basis for their practice.

If the secondary Victorian visual arts curriculum is based on the “child as artist” model, then it seems antithetical to Hale’s vision of finding a master instructor, for if the child is already an artist they do not require instruction (VCAA, 2017). To a degree, teaching skill-based drawing requires the teacher to be a “sage on the stage” by giving thorough explanations and demonstrations, and to model best drawing practices to students (Woolfolk & Margetts, 2016). Therefore, the teacher must be able to carry out the drawing exercises that they are explaining, in order to be the More Knowledgeable Other (MKO) and to scaffold students into their Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) (Vygotsky, 1978).

Due to the nature of skill-based drawing being situated in a step-by-step curriculum, as students develop procedural fluency in manual drafting, scaffolding can begin to be faded (Woolfolk & Margetts, 2016). However, teacher talk, modelling and scaffolding are necessary to ensure that students understand essential principles such as; light is form, shade is atmosphere (Graves, 2003). Ultimately, if students fail to develop competency in such foundational principles at any early stage, they will continue to struggle with the same principles as they progress with their training. In years seven and eight, students are generally aged between eleven and fourteen years old (this is the age that pupils in the Renaissance would begin their apprenticeships). According to Jean Piaget’s stages of cognitive development; at this age students fall under the concrete operations stage, where they are able to carry out logical thinking through referring to concrete objects in space (Woolfolk & Margetts, 2016). Therefore, it would be advantageous for the teacher to model foundational drawing principles through using concrete objects such as; a white sphere and a torch, to literally show how light effects form and to explain all the elements of light to students. Other concrete objects such as; a hand held plumb line (knitting needle) can be used by students to sight angles on their subject (the hand held plumb line is a tangible way of getting a sense for the scale of the subject). This will ultimately help them understand how long the subject is as opposed to how wide.

In years nine and ten, skill-based drawing allows students to undertake hypothetic-deductive reasoning as they develop through Piaget’s formal operations stage (Woolfolk & Margetts, 2016). More complicated principles of composition and design can be introduced to students including; how perspective, ratio and geometry can be used to solve pictorial problems. This ultimately provides opportunities to engage in Problem-Based Learning (PBL). For instance, students may carry out group research to uncover issues related to composition such as; how the golden section system of design and the Fibonacci sequence have been used by artists throughout the centuries (Costantino, 2002). At this point in their development, students will

also come to understand how drawing can be applied to fields outside of the visual arts such as; science (to document processes and experiments); design (to note down ideas and concepts); medicine (to teach perceptual skills in diagnoses); anthropology (as a way of taking field notes); technology (to create prototypes); and architecture (to visualise potential buildings) (Chand, 2016).

Inclusion into the Victorian Visual Arts Curriculum

For skill-based drawing to be successfully adopted by schools, there are several pieces of equipment and tools that are necessary for the proposed academic drawing curriculum to be taught effectively (see appendix 3). Ideally, it would be advantageous if the school has adequate funding in place in order to purchases these necessities. By far, the most important decision a school will need to make is deciding whether they will invest in one of the greatest educational resources, that have been available to Western artists for more than five hundred years; a collection of plaster casts from antiquity. From the Renaissance, through to the nineteenth-century, plaster casts of classical sculptures were considered idealised models that art students could use to study proportion, volume, anatomy and value (Aymonino & Lauder, 2015). During the early twentieth-century, the advent of modernism begun to change artists’ minds on the fact that the sculptures were the “ideal” and this resulted in many museum cast collections being sent to storage, or to be destructed (Leibold, 2010). Today, quality plaster casts are hard to come by due to the majority of museums no longer allowing sculptors to make new moulds of their collections and thus, causing artists to create lesser “homemade” casts, which are now available on the market (Valeri, 2013). If a school decides to invest in a plaster cast collection (to ensure they are of the finest quality), it is recommended that they are purchased from one of the following suppliers: Giust Gallery in Massachusetts; Felice Calchi in Rome; or, Orlandi Statuary in Chicago.

The art classroom that will be used for skill-based drawing will need to have A-Frame studio easels with drawing boards available for each student, as well as still life stands. Preferably, the walls of the classroom will be painted neutral grey, as opposed to white. This is because white walls bounce far too much reflected light into the shadows of the subject (painting the walls neutral grey keeps the shadows dark so the subjects form is accentuated) (Valeri, 2013). It would also be beneficial for the classroom to have north facing windows to create a cool and constant natural light source, or a skylight (art studios from the seventeenth through to the nineteenth-century used this lightening set up) (Aristides, 2011). However, if neither of these options are available, then artificial lighting will be sufficient. It is recommended that the classroom uses strong, white, full-spectrum bulbs with a Colour Rendering Index (CRI) that is higher than ninety (this will create artificial light which imitates daylight) (Valeri, 2013). If more light is needed due to a cloudy day; a desk lamp can be attached to the AFrame easels with a clamp. Teachers need to keep in mind that the proposed academic drawing curriculum involves exercises that can take several weeks to complete. Therefore, the classroom must have ample storage space for students works in progress, as well as enough space for them to set up their easels and subjects.

Practice and time are two factors that are of the utmost importance in order to develop dexterity with skill-based drawing (Aristides, 2006; Hale, 1964; Gammell, 1990). As was previously stated, the majority of contemporary teaching studios which are patterned after the French academic curriculum offer programs which range from three to five years in length (Graves, 2003; “Study-four-year”, n.d.). Students work on exercises so long as they remain productive and progress at their own pace through the curriculum (Graves, 2003; Gutteridge, 2016). Emphasis is given on quality rather than quantity therefore, students are required to bring their drawings to a height level of finish before progressing onto the next exercise. Due to the time allocated to the subject of art within a school’s timetable, there may not be enough contact hours per week for students to get through all the exercises prescribed in the proposed academic drawing curriculum. Therefore, teachers may need to incorporate non-formal learning into their teaching to allow more time for students to complete the exercises.

Non-Formal Learning

Coombs and Ahmed (1974) first used the term, “non-formal learning” to describe a way of imparting knowledge that does not necessarily have to take place in one set context, or be measured over a period of time, but rather, can take place in a number of settings; “regardless of where, how or when the learning occurs” (p. 8). Reddy (2003) identifies non-formal learning as; “activities outside the formal learning setting, characterised by voluntary as opposed to mandatory participation” (p. 21). The process of teaching through using the nonformal learning model is systematic and generally involves pre-planning (although not always necessary), so that the lessons agenda is clear for both teachers and students (Mok, 2011). Mok (2011) states; “modes of assessment and intended learning outcomes have not been clearly outlined in non-formal learning” (p. 13). This allows the teacher more flexibility with the lessons objectives, by not having to be overly concerned with meeting learning outcomes that would otherwise be strictly abided by with formal learning. La Bella (1982) notes that an effective way of implementing non-formal learning in secondary schools is through extracurricular activities.

The concept of non-formal learning lends itself well to teaching skill-based drawing and provides an answer to the aforementioned issue of time. Hypothetically speaking; a teacher could provide students with the option of undertaking extracurricular learning after school, during lunchtime, on weekends, or on school holidays. The fact that assessment is not necessarily of key importance will take the pressure off students, and this may result in them finding skill-based drawing to be enjoyable (Mok, 2011). Consequently, students that take advantage of the extracurricular classes will be attending on their own terms therefore, they will genuinely be interested in improving their work.

Professional Development

Art history reveals to us that the training a student received from their teacher was detrimental to their formation; without Ghirlandaio there would have been no Michelangelo; without Verrocchio, no Leonardo. Therefore, it is critical that the More Knowledgeable Other who is teaching skill-based drawing has adequate experience with the subject themselves (Vygotsky, 1978). Although the proposed academic drawing curriculum gives a theoretical explanation of the exercises, it is up to the teacher to ensure that students are grasping the principles. This ultimately requires the teacher to have a more developed eye, to pick up on mistakes in students work and to then help them correct their errors, before they become habits (Ackerman & Parrish, 2011). If the teacher has little experience with skill-based drawing, then it is essential that they carry out professional development in the area. As was previously stated, in comparison to Europe and America, Australia does not have the amount of teaching studios that offer instruction in skill-based drawing (Gutteridge, 2016). However, the following schools and artist societies do offer some: Julian Ashton Art School in Sydney; Rob Gutteridge School of Classical Realism in Adelaide; Atelier Art Classes in Brisbane; Victorian Artists Society in Melbourne; and Twenty Melbourne Painters Society also in Melbourne. These institutions share a lineage with the Western European academic tradition and the tonal realist movement, which was founded in Australia by Max Meldrum during the nineteenth-century (McGrath & Smith, 1986).

The Da Vinci Initiative also provides professional development opportunities through workshops offered in various states throughout America, and their website which contains free skill-based lesson plans, classroom resources and online classes for art teachers located outside of the United States (Trippi, 2016). The Initiative supports the claim that teaching skills is a way to quantify cognitive development, through providing students with the technical understanding they need to communicate effectively (Kilarski, 2017; Kralik, 2014).

There are several texts which can additionally be used to provide art teachers with professional development. The books that are recommended are authored by Juliette Aristides (an artist-teacher who is a leading figure in the revival of classical painting and is also a cofounder of The Da Vinci Initiative) (Kralik, 2014). Aristide’s books include: The Classical Drawing Atelier; The Classical Painting Atelier; Lessons in Classical Drawing and most recently; Lessons in Classical Painting (Aristides, 2006, 2008, 2011, 2016). These books are key resources which have contributed to restoring a body of knowledge that was prevalent, prior to twentieth-century visual arts education. Historical information on the academic tradition and insight into the current revival of skill-based art is provided, as well as a series of exercises which are explained in a step-by-step manner. The books also have the added advantage of being published recently, which provides art teachers with language that is contemporary and easy to understand.

The Significance of Aesthetics

Aesthetics is an area of study that is highly opinionated which Dickie (1997) refers to as “an untidy discipline” (p. 109). The term “aesthetic” was coined in the eighteenth-century by the German philosopher, A. G. Baumgarten and indicates a category of philosophy concerning the study of artworks and beauty (Heid, 2005; Shelley, 2009). Abbs (1991) notes that in the twentieth-century, aesthetics had come to be affiliated with the process of making, responding and having extensive knowledge of art. To come to a further understanding of aesthetics, it would be beneficial to understand its antonym; anesthetic. This term is affiliated with a drug that is administered to numb the senses during surgery, conversely, an aesthetic is something which stimulates the senses. Each of the five senses share a relationship in such a way that when one is aroused, it triggers an emotional reaction which can be considered an aesthetic experience (Flannery, 1977). Heid (2005) explains that the results of such experiences improves our cognitive capacity, as we come to encounter things more intensely. Fundamentally critical in understanding aesthetics, is that essentially it involves interacting with the world and experiencing the miracle of life (Scruton & Lockwood, 2009). For instance, an aesthetic experience has the capacity to elevate the mundane activities of day-today life into unique moments of consciousness (Heid, 2005). Greene (2001) argues that through developing sensitivity to art and the visual world around us, we are able to find a more intense presence within ourselves and the world we live in. Such understanding allows for a heightening of imagination, curiosity and passion, which ultimately manifests into sublime experiences (Greene, 2001).

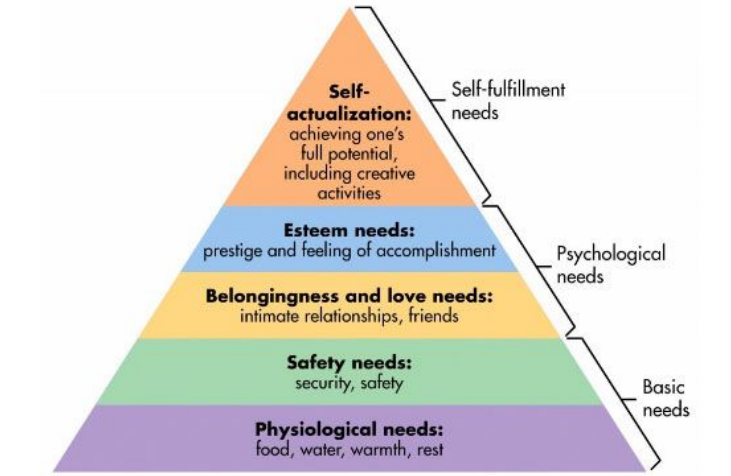

The Ancient Greek Philosophers were well aware of the power of beauty and its connection to goodness; they used the word kalakagathia to describe this relationship (Efland, 1990). Scruton and Lockwood (2009) identify that between the years 1750 and 1930, the objective of the arts was to express this very idea of beauty. According to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, all human beings are programed to meet basic requirements such as; consumption and safety (see appendix 4) (“Maslow’s hierarchy”, 2014). However, they also seek to meet higher spiritual and virtuous needs as well and if they are not met, human beings will ultimately become unsatisfied (Scruton & Lockwood, 2009). Many people experience a heightened sense of reality in their day-to-day activities, where they begin to see beyond the usual through an altered state of reflection. This can be triggered by; “a flash of sunlight, a remembered melody, the face of someone loved—these dawn on us in the most distracted moments and suddenly, life is worthwhile” (Scruton & Lockwood, 2009, NPN). These examples are the manifestations of beauty into an aesthetic experience which become transcendental. Graves (2014) likens the experience of art to a similar aesthetic experience that the majority of people have throughout the course of their lives;

“We truly feel great art, it’s an experience that cannot be described, like falling in love. It’s common to all of us but it’s individual—falling in love—different for everyone, but similar, because we read about it—we think about it—we connect. Beauty is the plate that these feelings are served up on, it holds the substance that allows us access to the nourishment we enjoy in the experience of art” (Graves, 2014, NPN).

One of the problems with presenting ideas of beauty in the art classroom is the confusion teachers have between the subjects of aesthetics and art criticism (Heid, 2005). Ishikawa (2014) validates this claim by stating that some teachers “are not familiar with art history and they do not understand the way of instructing art appreciation” (p. 209). Equally problematic is the fact that visual arts curriculum tends to place art history and art criticism together, within the same strand, which suggests that they are indistinguishable from one another (VCAA, 2017; Heid, 2005). It seems logical that in order for teachers to promote aesthetic experiences, they must provide teaching that improves their students skills in observation. Dewey (1934) discovered that the audience who is observing a work of art can experience what the artist felt at the time it was created, through studying the relationships between the formal qualities exhibited in the artwork. Moreover, Dewey believed that mundane experiences have the potential to become aesthetic experiences, regarding the viewer is fully present in the moment.

When we observe works of art, what we see is frequently determined by what we know. Therefore, teacher-led discussions can help foster unbiased responses from students which enables them to have pluralistic views on the subject matter (Duh, Zupancic & Cagran, 2014). The issue with carrying out a visual analysis that is based on the premise of “what do you see”, is that comments become increasingly personal which creates a mirror to each student’s cultural background, experiences, environment and lifestyle (Hino, Iwasaki, Ueno, Okazaki & Okumura, 2008; Broudy, 1972). Although these responses are beneficial in developing students critical thinking skills, they are merely subjective interpretations which become removed from what the actual message of the artwork is. Due to the nature of contemporary art occupying a space of hyper criticality, art teachers often see art criticism as a quintessential element in getting their students to talk about art (Smith, 2006). This is very much the way that art theory is taught at university level; students do not receive training solely in art history, nor do they receive training fundamentally grounded in art criticism, rather, they undertake a subject which combines these two areas into one which is called; Critical and Theoretical Studies (“Critical and theoretical”, 2017).

To address the subject of aesthetics in the art classroom, several issues must be rectified. Firstly, art teachers need to familiarise themselves with the theoretical underpinnings of historical artworks and secondly, the study of aesthetics needs to be taught in tandem with practical exercises. This will enable students to discriminate between art and craft and come to the realisation, that the former has always had some underlying philosophy governing its creation; be it Platonic ideas concerning beauty, or Greenbergian principles based on formalism. It is also important to draw the distinction between aesthetics and art criticism. For art criticism is based, to a degree, on ignorance as it is formulated on a subjective opinion which ultimately leads to judgment (Feldman, 1994). Conversely, aesthetics is an experience of the senses and as Dewey (1934) justified, the very fodder for an aesthetic experience is to remain open-minded and receptive to stimuli.

Inclusion into the Victorian Visual Arts Curriculum